Mass testing is being publicized approach of acceptance us greatly closer to a usual life and even of avoiding lockdowns in the future.

Testing everybody – even those without symptoms – can be a very dominant tool for digging out the virus.

Boris Johnson has pledged a “massive expansion” in such testing in the UK and Liverpool is the first city to trial it.

But questions have been asked about the current tests and the overall policy. So, what can mass testing credibly complete?

Sir John Bell, from the University of Oxford, is the government’s counselor on life sciences and he declares it “may well keep us out of trouble” but it is “very important we don’t over-hype”.

The promise of mass testing

Mass testing is alike to cancer screening – you can take healthy persons and test them and then you act early if there are any problems.

But instead of judgment the unseen cancer, you catch the people who have the virus who might not know it yet.

The expectation is this can be used to stamp out an epidemic, by getting everyone who tests positive to isolate, without turning to strict boundaries.

China has done this on multiple occasions by mass testing everyone in a city after a collection of cases was spotted. Slovakia is attempting this across the entire country.

There are also additional targeted ways of consuming mass testing:

- Regular testing in a hospital or care home could avoid an epidemic between people who are at the highest risk of Covid-19

- And it could keep places where the virus can spread, like cinemas, restaurants, schools and universities, open

- Additional option is a one-off test before being able to go to the cinema, theatre or a football match

“These tests will come online, they will be good and they are what we need, but we need to realize how fine they work and not over-promise on them,” said Prof Jon Deeks, from the University of Birmingham.

Mass Testing Technology

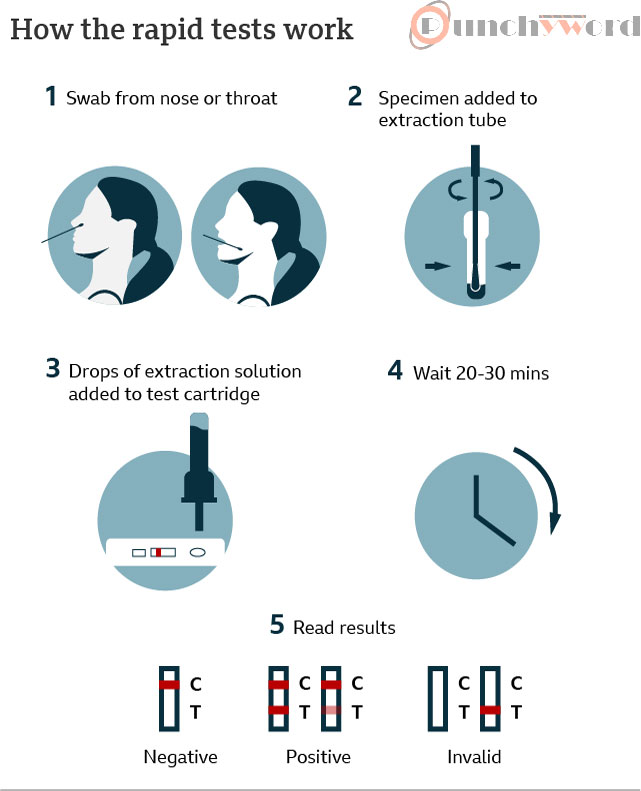

Single piece of kit has permitted the idea of mass testing to happen. It is called a lateral flow test which quickly perceives parts of the coronavirus itself.

These are similar to pregnancy tests and are cool, inexpensive and fast.

Fluid from a nasal swab or saliva goes on one end, and then a marking appears if you are positive. No experts or laboratories are required.

Speed and simplicity vs accuracy

The speedy tests are not as accurate as the current, lab-based PCR tests that hunt for wreckages of the virus’ genetic code.

“They are not flawless, if you invented they are ‘PCR in a stick’ we’ll end up with all kinds of trouble,” Sir John told.

The full results on the usefulness of the speedy tests have not been released.

Sir John, who is counseling the administration, said between one-in-500 and one-in-1,000 persons would be told they had the virus, when they did not.

This is an significant figure because “false positives” can become a problem when regularly testing large numbers of people. Test 60 million people twice a week and it adds up to nearly a quarter of a million persons wrongly told to isolate every week.

He also said the tests correctly identify 90% of diseased people if they had high levels of the virus in their body, but only 60-70% overall. Which figure is more useful is debated.

“Will there be people who are potentially infectious who test negative? Yes,” said Sir John. “I suspect that will happen and it won’t happen very often.”